A noted illustrator and painter of the American west and long-time resident of Covington. Henry Farny was born on July 15, 1847 in Ribeauville, Alsace, France to Charles and Jeanette Farny. The family immigrated to the United States in 1853 as a result of political strife in France. From 1852-1859, the Farny family resided in Warren, Pennsylvania. While in Pennsylvania, a young Henry came into contact with the Seneca Indian Tribe. Farny’s fascination with these Native Americans would become a life-long obsession. In 1859, the Farny’s moved to Cincinnati. Henry attended Woodward High School until the death of his father in 1861. Henry Farny held several early jobs. At the age of 18 he began producing illustrations of the City of Cincinnati for Harper’s Weekly. Farny also had worked as an apprentice in a lithographic shop in Cincinnati. In 1866, Farny decided to fully pursue a career in art. In that year, he traveled to Europe, visiting Rome, Dusseldorf, Vienna and Munich. He remained on the continent for more than three years, viewing and studying some of the greatest artworks ever produced.

Farny resumed his illustrating career upon his return to Cincinnati. He produced works for many of the popular periodicals of the day. In 1879 he was chosen the chief illustrator of the McGuffey Reader Series. Of the 300 illustrations produced, 76 were original works of Farny. During the 1880s, Henry Farny began a painting career that would last for more than three decades. Native American culture and history were gaining popularity in the early 1880s. Much of this can be attributed to the surrender of Sitting Bull to the United States Government in 1881. The news articles concerning Sitting Bull brought back many memories of the Seneca from Farny’s childhood in Pennsylvania. These memories led to a trip to the western territories in 1881. Farny’s fascination with Natives Americans was rekindled on this trip. Farny made dozen of sketches and purchased many photographs on his journey. He brought these items back to Cincinnati and began working on a series of paintings and illustrations depicting the life of the native peoples. The first painting in Farny’s western series was titled, “Tribes of the Plains.” The painting sold immediately. Many paintings of Native Americans followed. In 1883, Farny took another excursion to the west. On this trip, he was able to meeting the famous Chief Sitting Bull. Farny also became friends with General (later President) U.S. Grant and President Theodore Roosevelt. Several more trips to the west were undertaken in the 1880s. These trips not only inspired Farny’s work, but also filled his sketchbooks to overflowing. Farny’s depictions of the Native Americans were done in a very sympathetic manner. The Native Americans were always portrayed in realistic settings that were sensitive to their culture and traditions. Unlike many western painters of the day, Farny painted the everyday events of native life – not sensationalized battle and dance scenes.

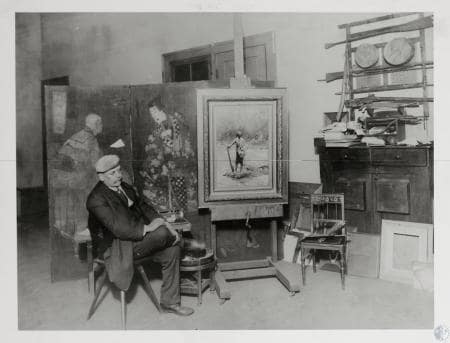

In 1894, Farny received the privilege of painting the portrait of Apache Chief Geronimo. Geronimo was so pleased with the work that he agreed to sign the canvas. In the 1890s. Farny moved to Covington. He used a double frame home at 1029-31 Banklick Street for his residence and studio. At this location, Farny entertained some of the most well known Cincinnatians of the day. In 1906, at the age of 59, Farny married his young ward, Miss Guerrin. The couple had one son, Daniel. Henry Farny died in 1916. Farny’s work has appreciated in value since the time of his death. In 1981, one oh his small paintings, “Peace and Plenty” (7 x 8 ¾”) sold in Cincinnati for $40,000. At this time, many of his larger works were selling in the $200,000 range. Many of his works are on permanent display at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Henry Farny’s home on Banklick Street slowly fell into disrepair following his death. By the 1980s, the building was in shambles.

In May 1984, the City of Covington Housing Director recommended that the building be demolished. Instead, Covington City Commissioner Denny Bowman began a movement to save the historic structure. A Kentucky Post editorial came out in support of the drive, “We fled to the suburbs years ago and left the old cities full of history to die. We tossed aside our heritage, letting decay erase our past, as we seized upon the future. And we have lost much in the process.” After a number of failed attempts to raise the necessary funds for restoration, the home was demolished on January 12, 1987.

Kentucky Post, May 2, 1984, p. 1k, May 3, 1984, p. 11k, May 4, 1984, p. 12k, May 7, 1984, p. 4k, January 13, 1987, p. 1k; Taft, Robert, Artists and Illustrators of the Old West 1850-1900. (1953); Local History Files of the KCPL.